Drug delivery capsule could replace injections for protein drugs

In recent years, scientists have developed monoclonal antibodies — proteins that mimic the body’s own immune defenses — that can combat a variety of diseases, including some cancers and autoimmune disorders such as Crohn’s disease. While these drugs work well, one drawback to them is that they have to be injected.

A team of MIT engineers, in collaboration with scientists from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Novo Nordisk, is working on an alternative delivery strategy that could make it much easier for patients to benefit from monoclonal antibodies and other drugs that usually have to be injected. They envision that patients could simply swallow a capsule that carries the drug and then injects it directly into the lining of the stomach.

“If we can make it easier for patients to take their medication, then it is more likely that they will take it, and healthcare providers will be more likely to adopt therapies that are known to be effective,” says Giovanni Traverso, the Karl van Tassel Career Development Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering at MIT and a gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

In a study appearing today in Nature Biotechnology, the researchers demonstrated that their capsules could be used to deliver not only monoclonal antibodies but also other large protein drugs such as insulin, in pigs.

Traverso and Ulrik Rahbek, vice president at Novo Nordisk, are the senior authors of the paper. Former MIT graduate student Alex Abramson and Novo Nordisk scientists Morten Revsgaard Frederiksen and Andreas Vegge are the lead authors.

Targeting the stomach

Most large protein drugs can’t be given orally because enzymes in the digestive tract break them down before they can be absorbed. Traverso and his colleagues have been working on many strategies to deliver such drugs orally, and in 2019, they developed a capsule that could be used to inject up to 300 micrograms of insulin.

That pill, about the size of a blueberry, has a high, steep dome inspired by the leopard tortoise. Just as the tortoise is able to right itself if it rolls onto its back, the capsule is able to orient itself so that its needle can be injected into the lining of the stomach. In the original version, the tip of the needle was made of compressed insulin, which dissolved in the tissue after being injected into the stomach wall.

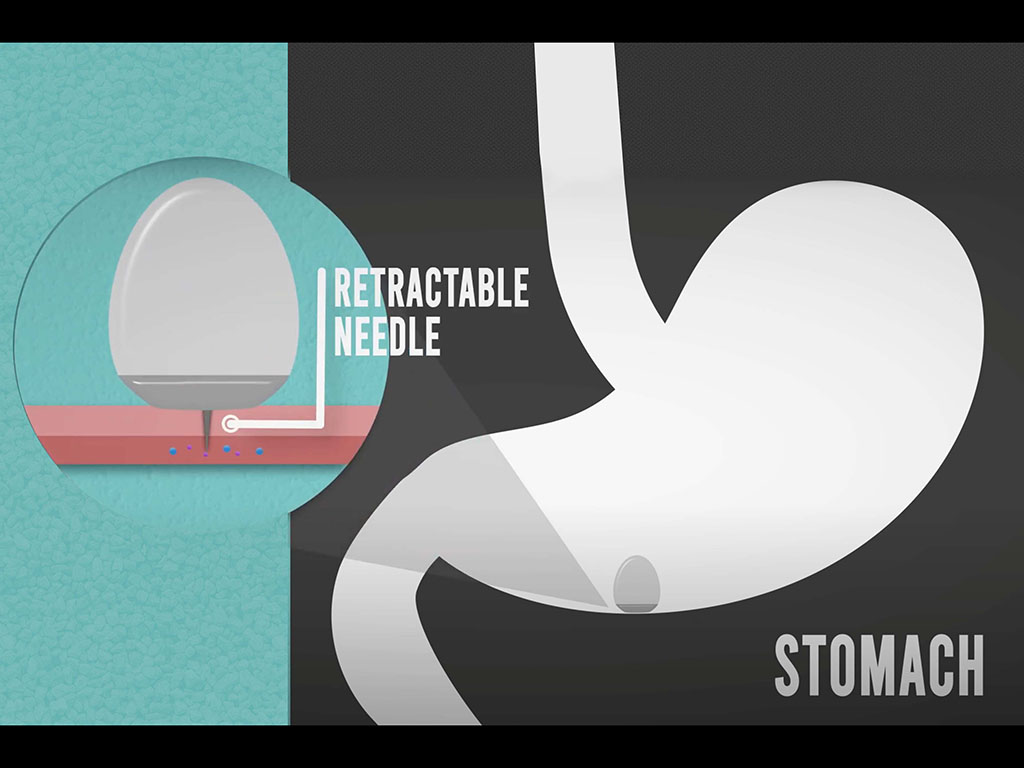

The new pill described in the Nature Biotechnology study maintains the same shape, allowing the capsule to orient itself correctly once it arrives in the stomach. However, the researchers redesigned the capsule interior so that it could be used to deliver liquid drugs, in larger quantities — up to 4 milligrams.

Delivering drugs in liquid form can help them reach the bloodstream more rapidly, which is necessary for drugs like insulin and epinephrine, which is used to treat allergic responses.

The researchers designed their device to target the stomach, rather than later parts of the digestive tract, because the amount of time it takes for something to reach the stomach after being swallowed is fairly uniform from person to person, Traverso says. Also, the lining of the stomach is thick and muscular, making it possible to inject drugs while mitigating harmful side effects.

The new delivery capsule is filled with fluid and also contains an injection needle and a plunger that helps to push the fluid out of the capsule. Both the needle and plunger are held in place by a pellet made of solid sugar. When the capsule enters the stomach, the humid environment causes the pellet to dissolve, pushing the needle into the stomach lining, while the plunger pushes the liquid through the needle. When the capsule is empty, a second plunger pulls the needle back into the capsule so that it can be safely excreted through the digestive tract.

Significant levels

In tests in pigs, the researchers showed that they could deliver a monoclonal antibody called adalimumab (Humira) at levels similar to those achieved by injection. This drug is used to treat autoimmune disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis. They also delivered a type of protein drug known as a GLP-1 receptor agonist, which is used to treat type 2 diabetes.

“Delivery of monoclonal antibodies orally is one of the biggest challenges we face in the field of drug delivery science,” Traverso says. “From an engineering perspective, the ability to deliver monoclonal antibodies at significant levels really transforms how we start to think about the management of these conditions.”

Additionally, the researchers gave the animals capsules over several days and found that the drugs were delivered consistently each time. They also found no signs of damage to the stomach lining following the injections, which penetrate about 4.5 millimeters into the tissue.

David Brayden, a professor of advanced drug delivery at University College Dublin, who was not involved in the research, described the new approach as “a very exciting advance for the potential oral delivery of macromolecules. That similar blood levels to those arising from injections of these types of drugs can be achieved by stomach administration to large animals is a technical landmark for the field.”

The MIT team is now working with Novo Nordisk to further develop the system.

“Although it is still early days, we believe this device has the potential to transform treatment regimens across a range of therapeutic areas,” Rahbek says. “The ongoing research and development of this approach mean that several drugs that can currently only be administered via parenteral injections (non-oral routes) might be administered orally in the future. Our aim is to get the device into clinical trials as soon as possible.”

Other authors of the paper include MIT’s David H. Koch Institute Professor Robert Langer, Brian Jensen Mette Poulsen, Brian Mouridsen, Mikkel Oliver Jespersen, Rikke Kaae Kirk, Jesper Windum, Frantisek Hubalek, Jorrit Water, Johannes Fels, Stefan Gunnarsson, Adam Bohr, Ellen Marie Straarup, Mikkel Wennemoes Hvitfeld Ley, Xiaoya Lu, Jacob Wainer, Joy Collins, Siddartha Tamang, Keiko Ishida, Alison Hayward, Peter Herskind, Stephen Buckley, and Niclas Roxhed.

The research was funded by Novo Nordisk, the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, MIT’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Division of Gastroenterology, and the Viking Olof Bjork scholarship trust.