Designing vehicles that drive, fly — and swim

When Crystal Winston was in elementary school, she carried around a notebook to jot down her ideas for new tools or machines. She was determined to become an inventor. Her dad nudged her in a more practical direction.

“He was like, ‘Yeah, I don’t know if inventor is a job,’” she laughs. “‘But maybe you could do mechanical engineering.’”

Now, a decade or so later, Winston has taken her dad’s advice to heart. This June, she’ll complete her degree in mechanical engineering. She is also one of five MIT students to receive the prestigious Marshall Scholarship, which provides two years of funding toward a graduate degree in the United Kingdom. And the field she’s going to study is not exactly traditional.

“When I applied for the Marshall, I pitched this whole idea that I was going to make a cool ecosystem of autonomous, flying, swimming cars,” she says.

A robot-driven future

Winston’s thesis, a project she started her sophomore year, was based on a revolutionary idea. She recalls being stuck in traffic on a bus in Atlanta, late for work, lamenting the congestion of motor vehicles. She imagined a world where transportation wasn’t limited to just roads.

“I had this idea for, basically, a flying car,” she says.

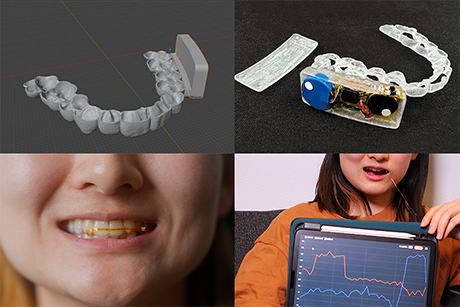

She texted a friend studying aerospace engineering, and the two came up with an idea for a small prototype of a car that could drive on the ground or lift off into the air. They are currently seeking a patent for their design.

Now a team of three, she and her collaborators, seniors Clarissa Sorrells and Noa Yoder, aim to one day add another capability to their flying vehicle: swimming.

“That’s been a longer-term goal. And it has also been the main reason why I applied for the Marshall: to do underwater, flying, swimming robotics research,” Winston says.

When Winston started this project, it was her first real experience with designing a robot start to finish. Now working in the lab of Associate Professor John Hart, she has been building and refining this robot for more than two years, along with her collaborators. She keeps photos of the prototype on her phone, showing the progress her team has made in constructing the potential transportation system of the future. It was while working on this project, she says, that she knew she wanted to be a mechanical engineer.

While the multifunctional car is her main research focus, she also did a robotics-related project through the undergraduate research opportunities program (UROP) in the Mechatronics Research Laboratory during her junior year. In collaboration with PhD student You Wu, she helped to build a rubber robot that could be put into a piping system, propelled by the flowing water, and detect any leaks as it mapped out the piping system.

In her first year, Winston also worked on creating a wearable blood pressure monitor through a UROP in the Research Laboratory of Electronics. More recently, she spent the summer before her senior year working with the team at Google responsible for engineering the StreetView cars. Her research focused on adding an infrared camera system to the cars so they could automatically detect when utility lines or transformers were at risk of going bad.

Engaging others in engineering

Since her first year at MIT, Winston has been involved with the National Society of Black Engineers (NSBE), which helps high school students who are members of underrepresented minorities in the Boston area apply for college — and build really cool stuff, like space balloons.

“We launched this giant balloon into near-space altitudes and took some really awesome photos,” she recalls.

In the years after that, during which Winston served as the NSBE’s academic excellence chair and then the programs chair, the students built Rube Goldberg-inspired machines and participated in robotics competitions. Working on programs for NSBE is where she’s spent most of her free time, she says. While she enjoys seeing all the projects and machines in action, for Winston it’s not just about space balloons — it’s about getting kids in the community excited about engineering.

Winston is also a member of MIT’s Black Students’ Union and recently served as a social chair for Tau Beta Pi, the mechanical engineering honor society. For TBP, she has organized events for members to connect and mingle with engineering faculty, as well as informational sessions for graduate students.

Outside of engineering, she loves to draw — and she’s really good at it.

“When I was in high school actually, I thought for a minute that I might go to art school, and write graphic novels,” she says.

In fact, one of Winston’s favorite classes at MIT has been the one she’s in now: 21W.744 (The Art of Comic Book Drawing). For the final project, she’ll have to produce a standard-length comic book about an original idea. She’s not sure what she’ll do yet, but she’s thinking of creating half of a two-part comic that’s like “The Boondocks,” a satirical commentary on the black experience, where her classmate and friend will create the other half.

Robots abroad

In the fall, Winston will start school at Imperial College London to earn a graduate degree in aerospace materials and structures. She’s never lived outside of the country, so the move will be a pretty big change for her. But she’s excited for the new things she’ll get to learn about England.

“I’m a foodie, and so I’m just curious what the food is like there. I’m also curious about what the black experience is like there, because I imagine it’s different from how it is here,” she says.

Winston, an entrepreneurship minor, aims to start her own business after she gets her PhD. One option she’s considering is starting a transportation-related company that designs or creates cars that can both fly and swim. Or, she might start a company that’s involved with search-and-rescue robots. Either way, she wants to stay involved with robotics and transportation. And if we want to find Winston’s network of robots in the future, it’s likely that we’ll only have to look up — or look underwater.